Nature has tried to tell us for a hundred years that we should remove from the scientific world-view the idea that the world around us is still there even if all aware inhabitants disappear. As I see it, we must finally learn the lesson that reality as we know it is observer-dependent in order to develop physics further.

Many physicists refuse to accept this conclusion, in part because they fear the implications. But there is no need to be afraid. To say that reality is observer-dependent does not imply that everything is subjective, nor does it imply solipsism. And it is still possible to do science in such a world. At least, this is what I argue in the present blog post.

Fruitful thoughts

It is not possible to prove that observers are indispensable in modern physics. But all attempts to understand the structure of relativity and quantum mechanics in a straightforward way without referring to observers have failed so far.

An even stronger hint that observers are indeed crucial is the fact that the original ideas that led to these theories revolve around observers, and the question what they can see, feel and measure. The fact that such ideas bear fruit must mean something.

The spark that inspired Einstein to formulate the special theory of relativity was a disturbing question that came to him already when he was sixteen years old. What would it be like to bicycle along a beam of light, at virtually the same speed? Would the cyclist observe a frozen light wave? In his Autobiographical Notes [1] Einstein writes

“From the very beginning it appeared to me intuitively clear that, judged from the standpoint of such an observer, everything would have to happen according to the same laws as for an observer who, relative to the earth, was at rest. For how should the first observer know or be able to determine, that he is in a state of fast uniform motion? One sees in this paradox the germ of the special relativity theory is already contained.”

In a lecture in Kyoto in 1922 Einstein described how “the luckiest thought” of his life came to him in 1907 [2], a thought that eventually led to general relativity in 1915.

“The breakthrough came suddenly one day. I was sitting on a chair in my patent office in Bern. Suddenly a thought struck me: If a man falls freely, he would not feel his weight. I was taken aback. This simple thought experiment made a deep impression on me. This led to the theory of gravity.”

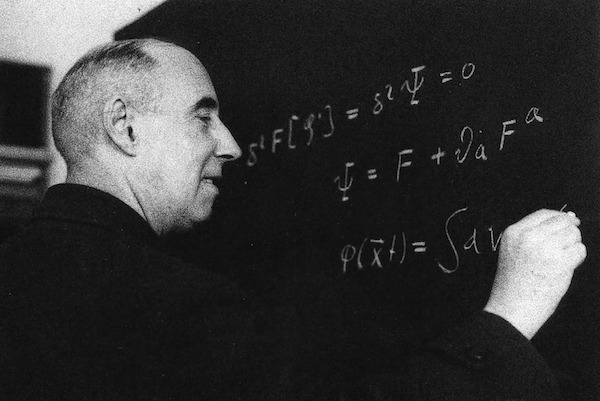

The breakthrough in the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics was a paper written by Heisenberg in 1925 [3]. Its abstract simply reads, in English translation:

“The present paper seeks to establish a basis for theoretical quantum mechanics founded exclusively upon relationships between quantities which in principle are observable.”

Heisenberg goes on to write:

“It is well known that the formal rules which are used in quantum theory for calculating observable quantities such as the energy of the hydrogen atom may be seriously criticized on the grounds that they contain, as basic element, relationships between quantities that are apparently unobservable in principle, e.g., position and period of revolution of the electron.”

The immense fruitfulness of these ideas is a hint as clear as any hint can be that we should walk further along the same road as we try to develop physics further.

Not so fruitful thoughts

Nevertheless, in recent decades many physicists have tried to walk in the opposite direction.

Some have supplemented the established formalism of modern physics with ‘hidden variables’ that describe entities with no direct relation to observations. Sometimes these entities are called ‘beables’, in contrast to the ‘observables’ that are sufficient to formulate standard quantum mechanics. (An example of a beable would be an electron which always possesses the well-defined position. This position would then be the corresponding hidden variable.)

Others are gluing the label ‘real’ on the mathematical tools that are used to express the laws of modern physics, like the wave function or quantum fields. These tools then become a more abstract form of beables.

Physicists playing with such models hope that they will be able to weave a fundamental layer of observer-independent reality from the thread defined by these beables. Observables and actual observations are imagined to emerge somehow as secondary phenomena out of the woven fabric. However, in order to conform with all the empirical facts, it seems that this fabric necessarily becomes very messy and ugly. Furthermore, as far as I am aware, such models have not led to a single new prediction confirmed by experiment.

The fact that these beables are imagined to be the only building blocks of the fundamental layer of reality means that observers are locked out from the construction by assumption. No surprise, then, that it is very hard to let them in afterwards through the locked door. Philosophers and physicists bang their heads against the hard walls defined by the fabric of beables, pondering the ‘hard problem of consciousness’ they have created themselves.

Some theoretical physicists concede that it is impossible to solve this ‘hard problem’. They admit that consciousness is an essential element of the world, but argue that it cannot be understood or described by science. In so doing they look upon conscious observers as immaterial spirits that can float through the walls of beables to become inhabitants in their house. It is odd that physicists accept the idea that there are essential elements in the world that lie outside science. It is even more odd that they seem blind to the fact that modern science already incorporate consciousness, in the sense that the basic postulates of quantum mechanics are formulated as a relationship between the observer and the observed.

Jenny Hasselquist and Lars Hanson as Marianne Sinclair and Gösta Berling, respectively, in the movie “Gösta Berlings saga” from 1924.

Jenny Hasselquist and Lars Hanson as Marianne Sinclair and Gösta Berling, respectively, in the movie “Gösta Berlings saga” from 1924.

Trying to escape from oneself

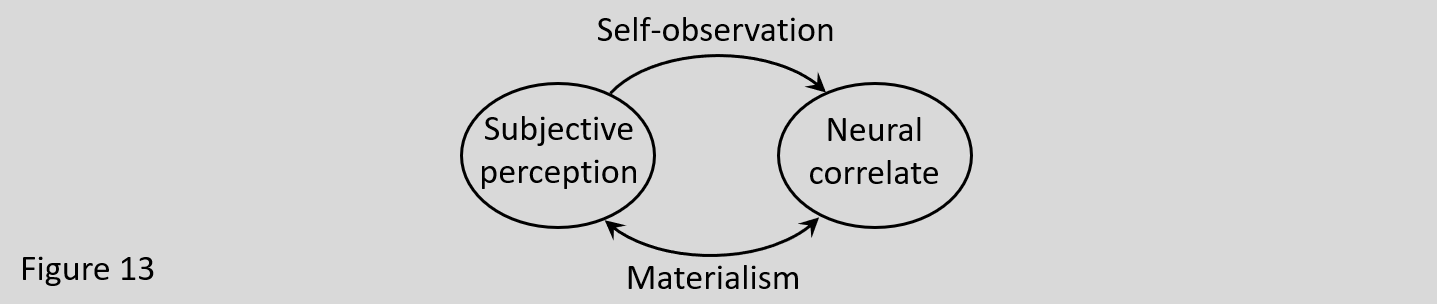

Instead of introducing beables in order to evade the conclusion that conscious observers are fundamental one may try to objectify the act of observation.

Naively, an observation always has a subjective side to it: someone observes something. Many physicists deny this fact by saying that it is sufficient as far as physics concerns to consider ‘observations’ made by a measuring apparatus. Such an ‘observation’ just amounts to an interaction between the system of interest and the apparatus. We might introduce a conscious physicist who in turn observes the pointer readings of the measuring apparatus after the interaction, but that is immaterial, they say. Alternatively, they claim that the observing physicist is equivalent to such an apparatus. This is the hard-core materialist approach. In either case, the driving force is the wish to objectify the observing subject.

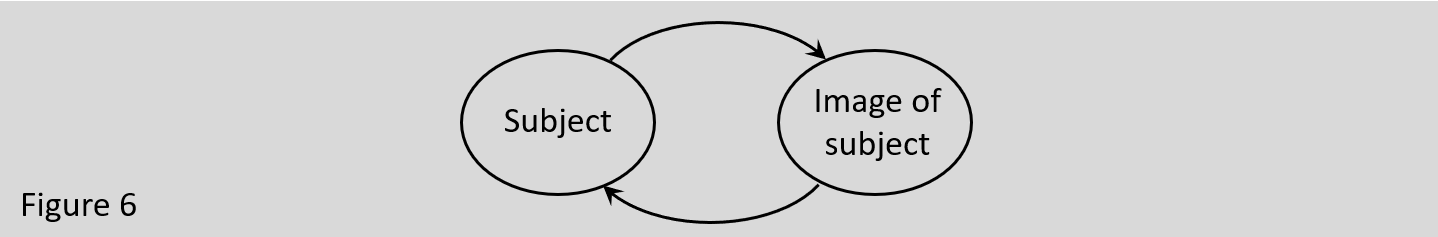

But we fool ourselves if we think that it is possible to look upon ourselves as observers from an outside objective position. The best you can do to transcend yourself is to hold up a mirror in front of you. But the picture that you see will still be created from within. You may position a second mirror to capture the image of yourself holding the first mirror, thus analyzing the interaction between a system of interest – yourself – and a measuring apparatus – the mirror. But the picture that you see is still created from within. You may introduce a third mirror to capture the entire scene, and so on. The more mirrors you introduce the smaller and more shattered will be the picture of yourself that you see in this hall of mirrors. But you are still stuck within yourself, even though your heart is shrinking. Genuine objectification of observations is impossible.

I come to think of the unhappy heroine Marianne Sinclair in Selma Lagerlöf’s novel Gösta Berling’s saga [4]. She played the mirror game all her life, trying to escape from herself, looking upon herself from the outside as an object of analysis – except one night when Gösta Berling came right at her and crushed all the mirrors.

“But we thought of the strange spirit of self-consciousness which had already taken possession of us. We thought of him, with his eyes of ice and his long, bent fingers,—he who sits there in the soul’s darkest corner and picks to pieces our being, just as old women pick to pieces bits of silk and wool.

Bit by bit had the long, hard, crooked fingers picked, until our whole self lay there like a pile of rags, and our best impulses, our most original thoughts, everything which we had done and said, had been examined, investigated, picked to pieces, and the icy eyes had looked on, and the toothless mouth had laughed in derision and whispered,—

‘See, it is rags, only rags.’

—

And if one looks carefully, behind him sits a still paler creature, who stares and sneers, and behind him another and still another, sneering at one another and at the whole world.

And while Marianne lay and looked at herself with all these staring icy eyes, all natural feelings died within her.

She lay there and played she was ill; she lay there and played she was unhappy, in love, longing for revenge.

She was it all, and still it was only a play. Everything became a play and unreality under those icy eyes, which watched her while they were watched by a pair behind them, which were watched by other pairs in infinite perspective.

All the energy of life had died within her. She had found strength for glowing hate and tender love for one single night, not more.”

Lagerlöf expresses how our “best impulses” and “most original thoughts” are picked to pieces by the pale creature. We may compare to the traditional scientific analysis of free will, where each impulse and choice is considered to be predetermined by the physical processes that go on in our brains. We look at the pale mirror image of ourselves and conclude that there is nothing original in our whims and ideas, that they are all secondary to electrochemical activity, which can be investigated and picked to pieces until nothing is left unexplained.

But this picture is challenged by quantum mechanics. The reason is the simple fact that its formalism take our own observations as a starting point, rather than processes that can be analyzed from a hypothetical objective, external position.

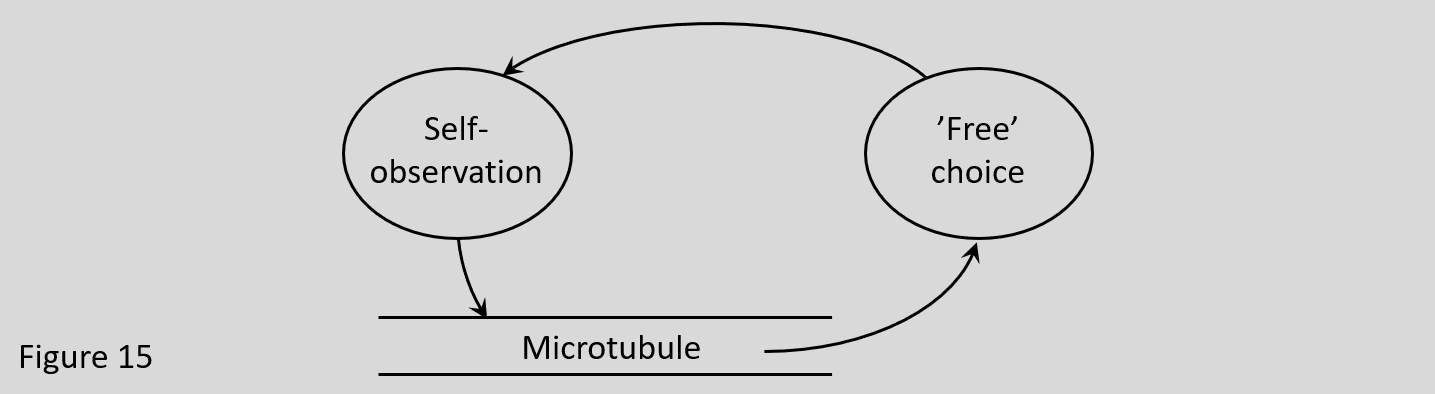

Quantum mechanics deviates from determinism at two levels. The observable outcome of a given experiment is not always determined beforehand. All we can do then is to assign probabilities to the different outcomes. We can apply this fact to our own brains and argue that some of our impulses and thoughts are not predetermined, but appear by chance with a given probability. We are dices in God’s hands.

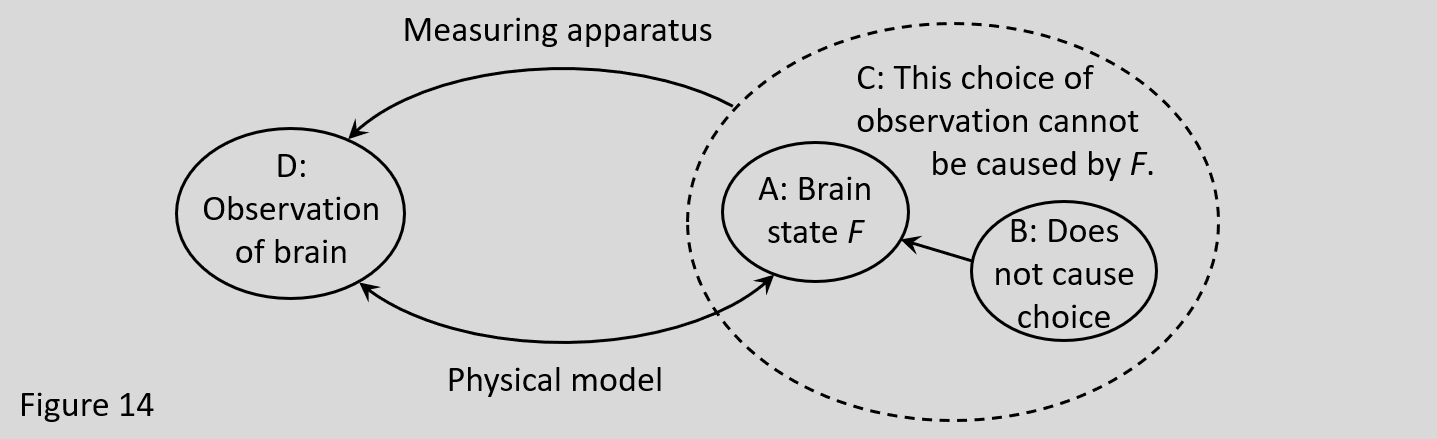

But there is an even deeper lack of determinism in quantum mechanics, which is not so often discussed. To be able to decide the probabilities for different outcomes, we must first choose which experiment we are going to do. And quantum mechanics remains silent about this choice. The theory is expressed in the form “Given that we observe a certain system in a certain way, the probability to see this or that is so and so.” If I look to my right I will see this or that with certain probabilities, and if I look to my left I will see this or that with other probabilities. But quantum mechanics does not say anything at all about which direction I will actually look. This is often called Heisenberg’s choice, and it lies outside the scientific description, as far as quantum mechanics can tell. Even so, it has tangible consequences; it affects the future evolution of the physical world.

Now we may try to evade this conclusion by calling on the pale creature to observe ourselves from the outside. Then we may say that there is a meta-experiment performed by the pale creature whose outcome determines which experiment we are going to choose. In the above example the outcome of this meta-experiment decides whether we are going to look to the right or to the left. If our pale creature dissects our brain well enough, he might be able to decide the probability of each outcome, saying that we will look to the right with probability 2/3 and to the left with probability 1/3.

But as the creature focuses on this task we must ask ourselves what on earth made the creature choose the particular meta-experiment that decides whether we are going to look to the left or to the right. We have to consider a meta-meta-experiment that decides whether we are going to do either of those things, or something completely different, like singing a song. Ah, but let’s call upon the still paler creature that sits behind the first creature to perform this meta-meta-experiment.

We may go on forever, creating an infinite tower of self-observing creatures, placing an infinite number of mirrors in the mirror hall. We still cannot escape the conclusion that we start with an original choice that is beyond scientific description, simply because this is the premise when we apply the deepest scientific theory that we have – quantum mechanics. Thus we can sweep away all these pale creatures and mirrors from the mind, like Gösta Berling did. We can acknowledge ourselves and the fact that there seems to be “original thoughts” and “best impulses” coming to us from God knows where.

This liberation of the mind is not possible in classical, Newtonian physics. It presupposes the existence of a external, objective position from which everything can be observed and analyzed in detail, and everything that happens can be determined beforehand, at least in principle.

We may thus characterize the difference between classical and modern physics by saying that the former disregards that we cannot escape from ourselves, whereas the latter acknowledges it.

Don’t be afraid

Are we deserted within ourselves if this interpretation of modern physics is true? Whom or what can we hold on to? My impression is that the unease caused by these questions, and the instinctive unwillingness to look for answers that follow, is an important reason why many physicists try to find another interpretation of modern physics, an interpretation that keeps close to the safe and familiar shore of classical physics instead of heading straight into deep waters. But there are tentative answers to the questions above, answers that point to another shore that may be more interesting and appealing than the one we left more than a hundred years ago.

What may an observer-dependent world mean?

Here’s my attempt to answer the pressing questions. My arguments are tentative, and some of them may appear ‘poetic’ or even obscure. My only aim is to make one or two readers say to themselves: “Maybe this might be reasonable after all. Let’s explore these matters further.”

To summarize, I will try to motivate seven claims about the observer-dependent world suggested by modern physics:

1) The truth is still out there

2) Science survives

3) We can still pick the radio to pieces to learn how it works

4) There is still an external world

5) You are not alone

6) It is not anthropocentric

7) It is as little mystical as a world can ever be

Let’s discuss these claims one by one.

1) The truth is still out there

Quantum mechanics suggests that we should not imagine physical objects with properties that transcend our ability to perceive them. Basically, all objects are objects of perception. But there must be something that transcends the mere perceptions in any well-defined world view. The very statement that all objects are objects of perception is a statement about the nature of the world that transcends the perceptions to which it refer. In fact, any statement about the world as we perceive it is a transcendental statement in this sense. And we must be able to talk about what we see, hear and feel. We must also assume the distinction between true such statements and false ones. This is perfectly possible in an observer-dependent world.

There are also forms of perception such as the passage of time into which all perceptions are placed. We cannot break these forms; they are immutable. In this respect they resemble the laws of physics. In my own research I try to establish a certain one-to-one correspondence between physical laws and forms of perceptions. These rules of the game define an objective world into which we are thrown.

2) Science survives

I talked about the laws of physics. Despite what some people think, we can still do science in an observer-dependent world. Science and realism have no direct relation to each other – science is a method to accumulate and structure knowledge based on observations, realism is a metaphysical idea that says that the objects that we see somehow exist even if there is nobody there to look at them.

3) We can still pick the radio to pieces to learn how it works

It is easy to arrive at the conclusion that if the objects do not have an independent existence, the things that we see are nothing more than visual effects in a kaleidoscope, random reflections in the pieces of a broken mirror. There is no depth to the picture, no underlying order, no persistence.

But this conclusion is false. It is possible to assign an identity to an observed object, and to uphold this identity as time passes if we track it continuously. We can speak about this given object disappearing out of sight, and then returning again, like the sun in the morning. If we let physical law act on an object that is observed at some point in time this law may simply tell us that the object will play hide and seek as time goes. But physical law will act differently on a hypothetical object that we have not yet observed. And it cannot be applied at all to an imagined object that is not observable in principle. That’s how I see it, at least.

We can learn more about such an identifiable object that we just take a superficial glance at to begin with. We may pick it apart to see what it is made of. This is still possible in an observer-dependent world. Just like it is possible to define the identity of an observed object in such a world, it is also possible to define the notion that it consists of smaller parts. In other words, if we consider two objects it is sometimes possible to say that one is a part of another. In mathematical language, we can uphold the notion of sets and subsets.

In the picture I am suggesting, the physical state of the object is defined by the knowledge we have about it, and physical law acts on this state to determine how the object evolves. The possibility to increase the knowledge about the object as time goes by makes it necessary to allow for a formulation of physical law that acts on the smallest parts of the object we can ever know about. Therefore the principle of reductionism may be valid in an observer-dependent world just like in an observer-independent one.

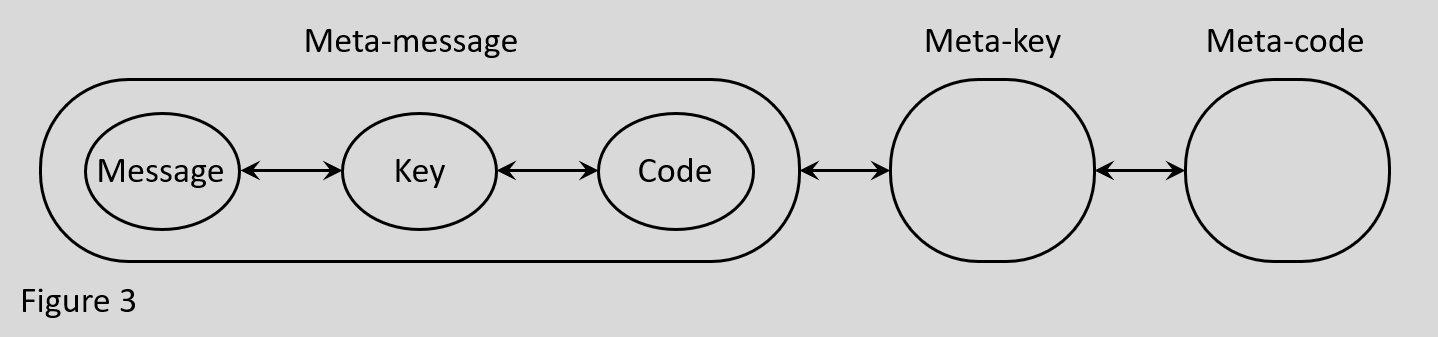

The notion that one observable object is a physical part of another defines a directed relation between them. One object points to the other. There are many more examples of such arrows between objects of perception. A generalization is an abstract object of perception that refers to the set of concepts it generalize. A memory is an object of perception that refers to an event in the past. A symbol is an object of perception that refers to the object it symbolizes, which is also an object of perception. A statement refers to a set of other objects and their internal relations. I think that the existence of such arrows between objects must be seen as part of the fundamental structure of the world. We cannot make them ‘emerge’ from the objects themselves – just as we cannot make conscious observers emerge from a fabric of beables. The world is simply delivered with a bag of such arrows, and also with a fundamental relation between the observers and the observed. The arrows make it possible to weave a world with rich structure, containing hierarchies and depths. Without them we are left with the structureless heap of pieces from the broken mirror I started out with.

4) There is still an external world

We all instinctively make the distinction between our own body and the external world. In the observer-independent world suggested by classical physics, the external world continues to exist even if the bodies of all conscious observers disappear. This is not so in the observer-dependent world suggested by modern physics. Nevertheless it is still possible to make the distinction between your own body and external objects in such a world. However, both your body and the external objects are basically objects of perception.

5) You are not alone

The most common reaction to the idea of an observer-dependent world is: “But that means solipsism!” This is not so.

The incorrect conclusion follows from the idea that observers should be identified with their bodies. As stated above, all objects are assumed to be objects of perception. But the only observer whose perceptions I have firsthand knowledge about is myself. Therefore I may argue that all objects are objects of my perception, including the bodies of other potential observers. If the bodies and the observers are identified their existence depends on my perceptions, and is therefore secondary to me.

However, there is a crucial difference between the idea that a person should be identified with her body, and the idea that everything she perceives corresponds to activity in her body. The latter idea contains the operationally relevant aspect of the concept of materialism. This type of ‘operational materialism’ may survive and thrive in an observer-dependent world.

In fact, the idea that an observer should be identified with her body is not consistent with the premise of the discussion, that the world is observer-dependent. Your own body is then an object of your own perception, just like body of everybody else. And you cannot identify yourself with a part of your own perceptions.

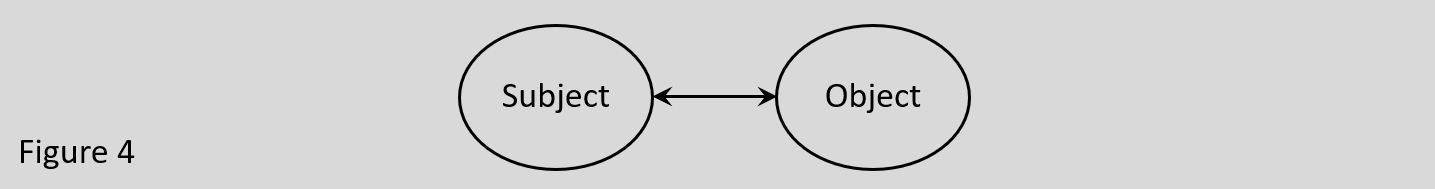

Let us therefore continue the discussion with the assumption that there is an aspect of ourselves that cannot be identified with our bodies. This means that we acknowledge both poles in the observer-observed pair, or the subject-object pair, and treat them both as fundamental. This does not mean that they can be separated from each other, like Descartes tried to do with his dualistic notions of res cogitans and res extensa; quantum mechanics is expressed as a relation between the observer and the observed, and if quantum mechanics is fundamental, so is this relation.

Then the subjective aspect of another observer can have an existence that is independent of your existence, even though her body is an object of your perception. She may have original thoughts and make original choices, in the sense discussed above, just like you. Having liberated the ‘souls’ of our fellow beings in this way, their bodies are also let free. Even though the body of the other observer may still seem secondary to you since it is an object of your perception, your body correspondingly becomes an object of her perception. You and your fellow beings are then placed at the same level ‘body and soul’.

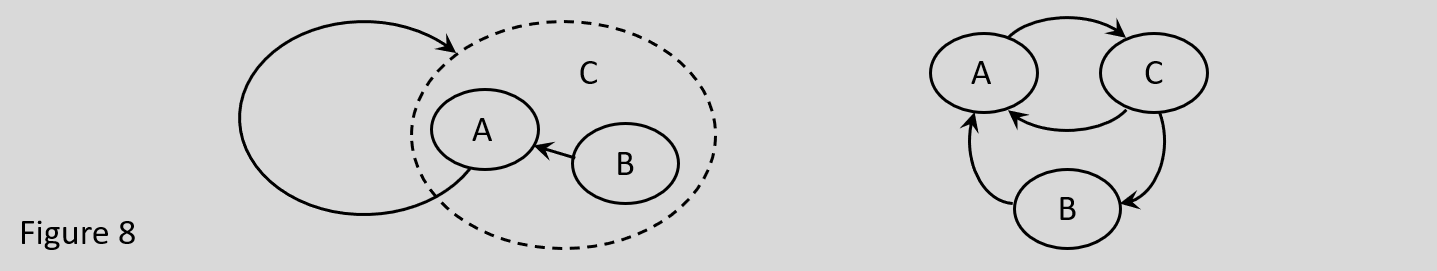

Let us explore these symmetries a little bit more. We have argued that it is perfectly possible to have a set of several subjects, which are equal in the sense that the existence of any one of them is not conditioned on the existence of any other. In an analogous way we know that we have a set of several objects in the physical world that are independent in the same sense: there are many apples in an apple tree, and if we eat one of them, the others do not vanish as well.

However, even if the members of the set of subjects are independent, just like the members of the set of objects, the two sets are not independent of each other. This is the core idea of a materialistic observer-dependent world. We have argued that all objects are objects of perceptions, and therefore they cease to exist if the set of subjects disappear. And experience tells us that our perceptions depend on our bodies. If the set of objects in our bodies disappear, so does the set of subjects.

Just like one subject may observe several objects, one object may be observed by several subjects. This symmetry between the subjective and objective aspects of the world may seem self-evident from everyday experience, but to promote it to a postulate makes it possible to use it to define the fundamental notion that several subjects live in the same world. They do so if and only if they sometimes observe the same object, be it an apple tree or each other’s bodies.

We may say then that this common world is defined by the sum or union of the perceptions of all the subjects that live in it, together with all the true statements they can make about their perceptions. In such a world physical law becomes a rule according to which this common state of knowledge about the world evolves.

We are clearly not alone in such a world. Our individual experiences and observations become a small part of its fabric. Just as we can divide the objective aspect of the world into small atoms, we may divide the subjective aspect into ‘small’ individuals. The word atom derives from the Greek word atomon, which means indivisible. The word individual is derived from the Latin word individuus with the same meaning. The fact that both the objective and the subjective aspects of the world can be described in a similar atomistic way supports the idea that they are symmetric to a considerable degree.

I have argued that it is possible to accomodate several observers in an observer-dependent world. But I have not yet given any argument why there should be several observers, apart from saying that it is natural for reasons of symmetry. I know of one such argument, at least.

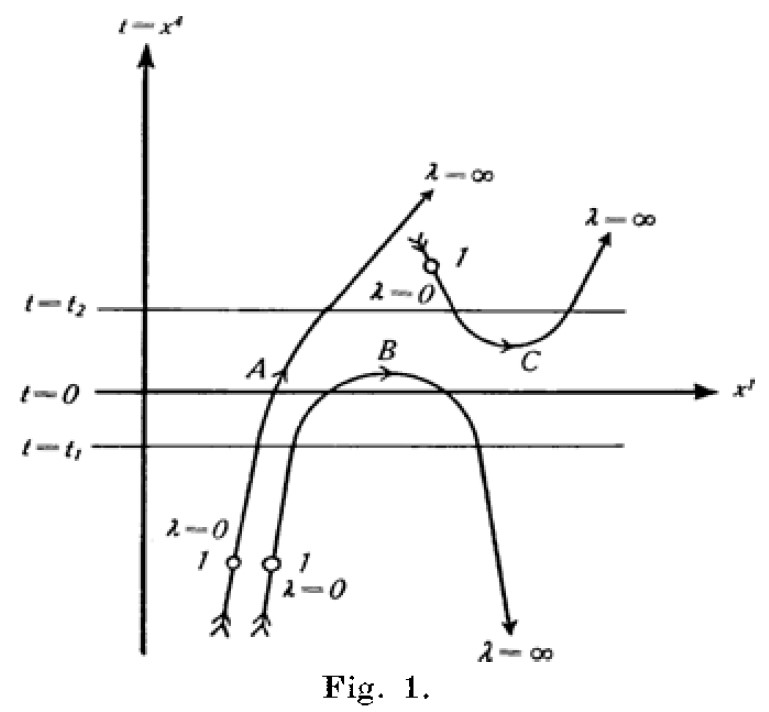

In special relativity, two observers can measure different spatial and temporal distances between a given pair of events, depending on how they move in relation to each other. The Lorentz transformation provides the recipe for how distances measured by one observer are related to the distances measured by the other. All equations that express physical law remain the same when a Lorentz transformation is applied to the spatio-temporal coordinates that are used to express them. This means that the measurements of all observers are equally valid, regardless their relative velocity, and that they are ruled by the same laws of physics.

My reading of all of this is that the world is constructed in order to accommodate several observers and to make them all equal – meaning that their measurements are equally valid even if they happen to differ from each other. The argument that leads to the Lorentz transformation presupposes two or more observers who observe the same object or event. The fact that the form of physical law remains the same when a Lorentz transformation is applied means that such situations are built into the structure of the world.

6) It is not anthropocentric

A common objection to the idea of an observer-dependent world is to say that it is anthropocentric. The reasoning goes something like this:

“Some people say that an experiment does not have a definite outcome before a physicist observes the result. Consciousness collapses the wave function and gets rid of its spooky superpositions. In other words, the state of the specimen that is studied in the experiment becomes real under the eyes of the physicist. But it’s ridiculous to think that we have to rely on human physicists performing experiments to make the world around us real.“

This reasoning is inaccurate in two respects.

First, consciousness cannot be seen as an agent that acts on something else, like a wave function. Such a dualistic conception is untenable. Rather, everything must be looked upon as consciousness, in the sense that all objects basically are objects of perception. The wave function collapse is just a formal description of the subjective increase of knowledge that occurs due to an observation in a controlled experimental setting.

Second, there are many other situations than scientific experiments in which our knowledge increases in a similar way. In fact, it occurs whenever a conscious creature makes a new observation, regardless whether it is a physicist, another human or an aware animal. Together we make the world real by our observations. We learn more about the perceived objects and new objects of perception come into our field of vision.

Not even in the lab does it matter who is making the observation. It is irrelevant whether the observer passed all her physics exams, whether she put on the white lab coat, or whether she is human at all. I would like to quote the prominent physicist Wolfgang Pauli [5], speaking about quantum mechanics:

“[T]here remains still in the new kind of theory an objective reality, inasmuch as these theories deny any possibility for the observer to influence the results of a measurement, once the experimental arrangement is chosen. Therefore particular qualities of an individual observer do not enter the conceptual framework of the theory.”

My working hypothesis is that the immutable forms of perception reflect the laws of physics, and vice versa. Examples of such forms of perception are the directed flow of time and the fact that objects can be divided into parts. If this hypothesis is correct, these forms are common to all conscious creatures that live in the same world, since all such creatures are governed by the same laws of physics. This is a comforting thought, I think. It would mean that all beings are brothers and sisters that look in a similar way at the world into which we are thrown. We can then understand each other at a basic level.

7) It is as little mystical as a world can ever be

Another common objection to the idea of an observer-dependent world is that it is mystical or approaches the ideas associated with ‘new age’. Some even say that it cannot be combined with science.

Such reactions do not in themselves form an argument against the idea. Rather, they express distaste. Science does not rely upon a specific metaphysical idea like realism, but on the empirical method, rationality, and the coherence and clarity of the concepts that are used to build models. I come to think about a quote by Darwin [6]:

“In scientific investigations it is permitted to invent any hypothesis, and if it explains various large and independent classes of facts it rises to the rank of a well-grounded theory.”

Put differently, it is not the content of a hypothesis that makes it scientific or not, rather its form. The new age movement has made a great disservice to hypotheses about the physical world that are centred around observations and consciousness, since they have become associated with the intellectual sloppiness and wishful thinking that is abundant in that milieu.

In an observer-dependent world, the history of the universe before the appearance of the first aware beings must be seen as an abstract extrapolation backwards in time using the laws of physics. The true creation is not the Big Bang but the first dim perception. There is no pre-existent physical world into which the first aware creature was born. Some people are repelled by this fact, and look upon it as a kind of creationism. The repulsion is another expression of the fear that science and spirituality will become intermingled.

I can understand the feeling that we lose firm ground to stand on if there is no pre-existent physical world into which we were born. But the firm, objective ground is still there, albeit in a more abstract form, as discussed under the headline “The truth is still out there” and onwards.

In fact, I would like to argue that such a ‘creationism’ is less mystical than the ordinary realistic and scientific story about the creation of the world. In that story we have two creations that cannot be explained in terms of something that was there before. First, we have the creation of the physical world in the Big Bang. Second, we have the appearance of consciousness when the first sufficiently complex creatures had evolved in this physical world. This second creation cannot be explained in terms of the first. That would amount to a solution to the hard problem of consciousness. This is impossible in principle since that problem is not properly posed, but the result of the untenable idea that it is possible to separate the observer from the observed in the dualistic spirit of Descartes. If we accept that the poles in this pair are distinct but inseparable we are left with just one mystery instead of two – the creation of both poles together.

I would say that the question whether an observer-dependent world is ‘mystical’ is a different one than the question whether consciousness is central. I would like to define mysticism as a belief in entities and realms of which we have no every day, tangible perception, and also the belief that these entities and realms are necessary to account for ourselves and the world in which we live.

In this sense those who feel the need to emphasize the existence of an observer-independent world are clearly mystics, since the realm in which they believe by definition cannot be reached by observation. Those of us who think that an observer-dependent world is sufficient are not necessarily mystics, on the other hand. We do have to believe in truth, objective physical laws and immutable forms of perception. Otherwise we fall in the trap of postmodernism. But these entities can be sensed and analyzed by ordinary means of perception, even though we do not have free access to the truth in which we believe, unfortunately.

Comfort: An observer-independent reality can never be ruled out

The statement that there is an observer-independent world is metaphysical. But so is the statement that there is no such world. From a scientific point of view both statements are meaningless. Anyone who wants to persist in the faith that there is an observer-independent world out there can therefore continue to do so regardless where science takes us in the future.

Even if the freedom to invent scientific hypotheses is large, as Darwin pointed out in the quote above, it clearly cannot be applied directly to such metaphysical statements. However, it can be used to address a related question.

It seems to me that one of the main lessons of quantum mechanics is that we should not represent the physical state of the world as if we know everything about it, as if we know the exact positions and velocities of all particles in the universe. If we do that we get the wrong answer when we ask physical law how the world evolves. This means that physical law acts on a state that corresponds to our incomplete knowledge about the world rather than on a state that corresponds to a perfect image of a hypothetical observer-independent world where all particles have definite positions and velocities. Simply put, physical law seems to act on our knowledge about the world, not on a hypothetical world in itself. If we try to feed it with metaphysics, it spits it out.

This idea can be promoted to a scientific hypothesis that can indeed be tested: physical law is such that if we feed it with data and entities that cannot be known or observed, then it spits out wrong predictions. I have given this simple principle a fancy name – explicit epistemic minimalism – and I claim that it explains various large and independent classes of facts in the words of Darwin.

This is a hypothesis that constrains the form of physical law; it is not a hypothesis about the world as such. However, if it is correct then the observed world of knowledge becomes self-sufficient to a considerable degree. Then we cannot use the laws of physics as a handle to open the door to the underlying observer-independent “real” world, since physics just refers to what we already know. But we do need such a handle to the underlying real world to be able to say anything intelligible about it; it must send an ambassador to our world of knowledge that can tell us some of its secrets.

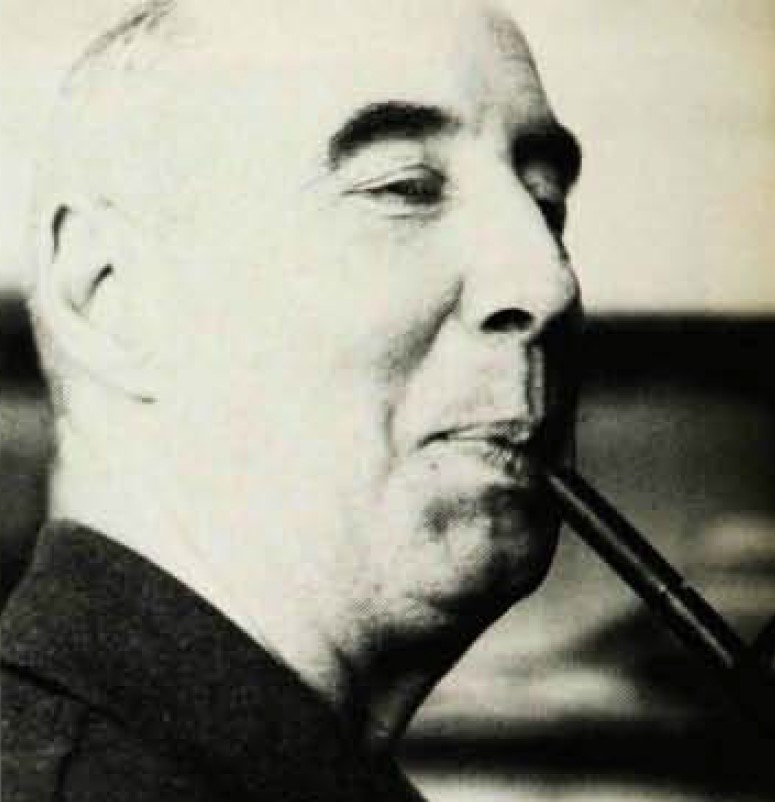

But the ambassador has not yet revealed herself. The underlying real world, if it exists in some sense of the word, therefore seems to have very little to do with the world that we actually observe. Many philosophers and scientists have arrived at the same conclusion. For example, Erwin Schrödinger wrote the following in his essay “My view of the world” [7]:

“Kant having established that the “tree in itself” is not only (as the English philosophers knew already) colourless, odourless, tasteless, and so on, but also belongs entirely to the realm of things-in-themselves which must in absolutely every respect remain inaccessible to our experience, we are in a position to declare once and for all that this thing-in-itself holds no interest for us whatever; that we are going, if necessary, to disregard it. Now, in the realm of things which do interest us, the tree presents itself just once, and we can just as well call this single datum a tree as a perception-of-a-tree – the first having the advantage of brevity. This one tree, then, is the one datum we have: it is at one and the same time the tree of physics and the tree of psychology. As we observed at an earlier point, the same elements go to make up both the Self and the external world, and in various complex forms are sometimes described as constituents of the external world – things – and sometimes as constituents of the Self – sensations, perceptions. These thinkers call this the restoration of the natural concept of the world, or the vindication of naïve realism. It does away with a whole mass of pseudo-problems, in particular the famous ignorabimus of Du Bois Reymond, of how feeling and consciousness could arise from a movement of atoms.”

Let the dead ones go

I don’t know if any believer in an observer-independent real world found comfort in the preceding section. Considering the development of physics during the last hundred years, such a belief, to me, resembles the belief that a beloved person who has died lives on somewhere, in some other realm. I do entertain such thoughts myself, sometimes.

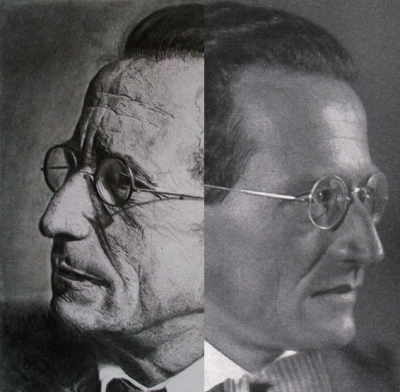

I don’t want to give the impression that it is easy to give up beliefs of this kind. Even those physicists who developed and championed the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics in the twenties did not arrive easily at the conclusion that physics only deals with appearances, with what we can say about the world rather than what is. For example, Werner Heisenberg expressed himself in the following way [8]:

“During the months following these discussions an intensive study of all questions concerning the interpretation of quantum theory in Copenhagen finally led to a complete and, as many physicists believe, satisfactory clarification of the situation. I remember discussions with Bohr which went through many hours till very late at night and ended almost in despair; and when at the end of the discussion I went alone for a walk in the neighbouring park I repeated to myself again and again the question: Can nature possibly be so absurd as it seemed to us in these atomic experiments?”

Maybe the shock felt by the physicists in the twenties when classical physics finally died after a long period of illness resembled the shock that we feel when an ill family member or friend finally passes away.

When a beloved person dies, the world as we know it is torn apart. But after a while we reconstruct it again so that it becomes similar to what it was before, but not quite the same. The latter process has been going on in the physics community in the last decades. Many physicists have recently turned their backs on the Copenhagen interpretation and tried to construct new interpretations of quantum mechanics that rely on modified observer-independent models of the world. They are not quite the same as the old Newtonian model, but they may nevertheless be called “classical”.

They cannot accept the death of classical physics, they cannot let go of the picture of the world that it painted. And now they think that they can bring it to life again. As we have discussed above we can never exclude the possibility that they are right. We can never exclude the possibility that the deceased loved one suddenly is knocking on our door again. But there is no sign of any such resurrection.

In the end, the metaphysical picture of the world associated with classical physics was just an imaginary friend. It was never there, it was all in our heads. There is no real loss. The world remains the same after it passed away. The only thing that has changed is our perspective. Physics can move forward only if we accept this new perspective wholeheartedly, I think.

References

[1] Albert Einstein, Autobiographical notes, translated and edited by Paul A. Schilpp, Open Court (1949)

[2] Albert Einstein, How I created the theory of relativity, translated by Yoshimasi A. Ono, Physics Today 35(8) pp. 45-47 (1982)

[3] Werner Heisenberg, Über quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen, Zeitschrift für Physik 33(1) pp. 879–893 (1925)

[4] Selma Lagerlöf, Gösta Berlings saga, Frithiof Hellbergs förlag (1891). English translation: Pauline Bancroft Flach, The story of Gösta Berling, Gay and Bird (1898)

[5] Wolfgang Pauli, Matter, in: Writings on Physics and Philosophy, edited by Charles P. Enz, and Karl von Meyenn, Springer-Verlag (1994)

[6] Charles Darwin, The variation of animals and plants under domestication, Volume 1, John Murray (1868)

[7] Erwin Schrödinger, Meine Weltansicht, Zsolnay (1961). English translation: Cecily Hastings, My view of the world, Cambridge University Press (1964)

[8] Werner Heisenberg, Physics and philosophy: the revolution in modern science, HarperCollins (1958)

Detail of Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus (1539)

Detail of Carta Marina by Olaus Magnus (1539)

Jenny Hasselquist and Lars Hanson as Marianne Sinclair and Gösta Berling, respectively, in the movie “Gösta Berlings saga” from 1924.

Jenny Hasselquist and Lars Hanson as Marianne Sinclair and Gösta Berling, respectively, in the movie “Gösta Berlings saga” from 1924.