This is an English translation of a blog post in Swedish published in 2017.

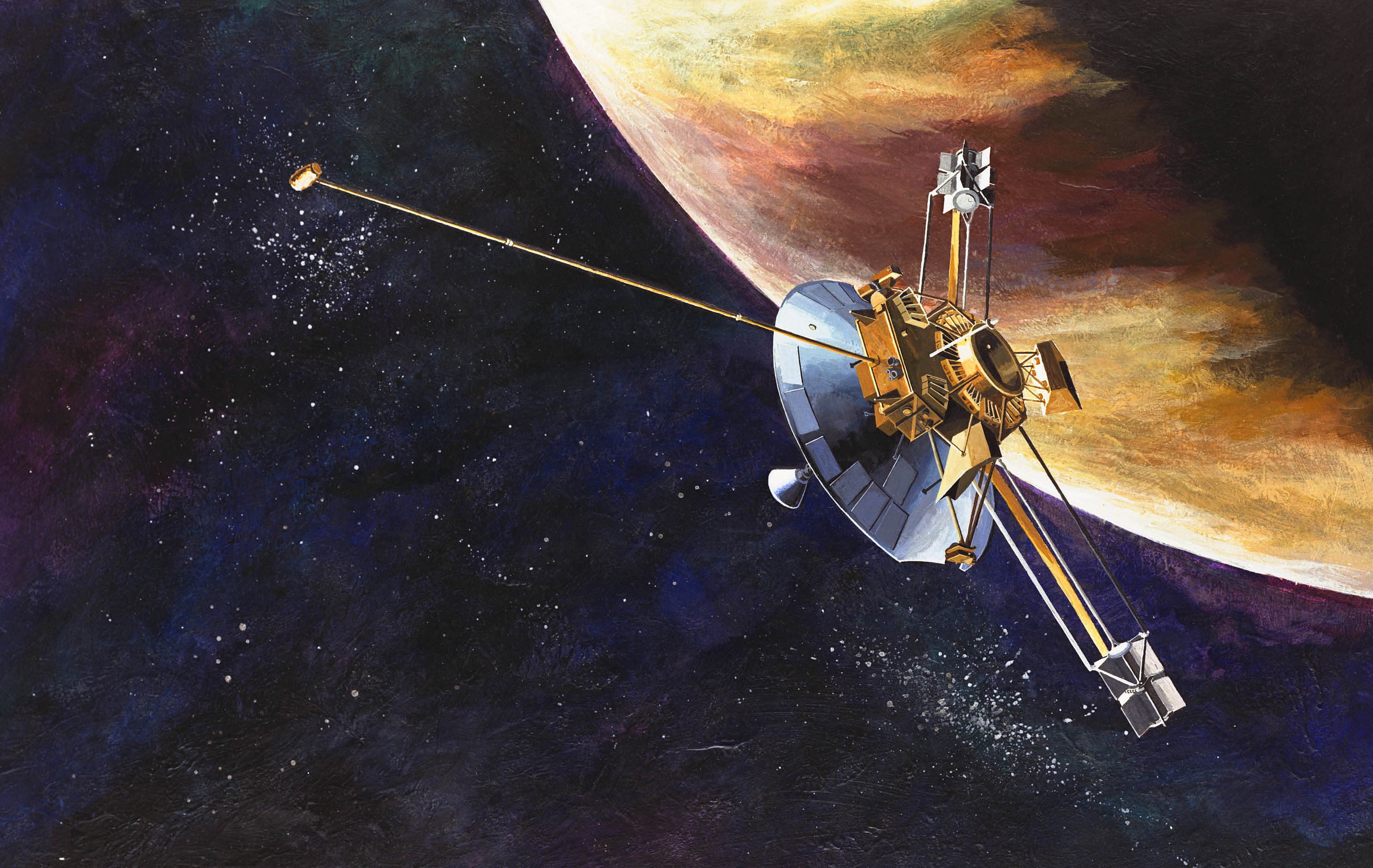

A summer day in the mid 70s I was sitting in my parent’s Volvo PV outside a public swimming pool in our home town Lund, Sweden, listening to the radio. My big sister attended swimming school. The voice on the radio talked about a space probe which had investigated Jupiter and its moons. In hindsight I conclude it must have been Pioneer 11. The existence of alien planets and the infinite space struck me with wonder and fear.

Much later I have pondered the strange fact that our familiar landscape with towns, fields and forests floats on top of bottomless seas of glowing magma. But this thought has not led to the same feeling of striking wonder as the thought of the planets in space did when I was three or four years old. It has not grown to much more than a thought.

To some extent it certainly has to do with age. Most of us become less receptive to immediate impressions as we grow up. We spin a cocoon around us weaved of thoughts about the world. On the inside of this cocoon we paint pictures of the outside. As time goes by we paint layer on top of layer of conceptions. They make it harder and harder to see and perceive the world – what we see are just our own conceptions of it.

It is the same thing with memories. Throughout my life I have been thinking about the radio broadcast about alien planets that made such an impression on me. That makes it hard to know if I really remember the event by now, or if I just reach my previous attempts to remember it, the pictures of the event I have painted as I lost access to the proper memory.

The ever thicker layers of paintings on the inside of the cocoon make it almost opaque. It becomes hard to feel the wind of the world through the threads out of which it is spun. Of course, that makes it harder and harder to paint accurate pictures of the world. Finally we just reproduce the pictures we have already painted, since that is the only thing we see. Even though we may the best of intentions, our world view deviates more and more from the world as it really is.

It seems to me that much of the follies in the world, and much of its misery, has its root in the fact that people ceases to see the world, ceases to see themselves, seeing only their own conceptions, hearing only their own statements about it. People who are blindly convinced of the goodness of the ideology they have painted in front of themselves and each other, can step on and crush innocent people without noticing it, feeling like walking on air, with a blessed smile on their face.

The blind conviction that you belong to the good side is most often associated with religion, but is sometimes ascribed to the political left. But the right suffers from a blindness of its own. People on the right can become so convinced that their own perspective is the only rational one that they do not see that other perspectives can be equally reasonable. They do not see that they, with reason as a beacon, go astray in ideological quagmires and sink into the irrational swamp.

If the political right sometimes confuses ideology with reason, materialists sometimes confuse their own world view with science. But science is just a method to gain knowledge. Whether science supports a materialistic world view can only be decided empirically. The answer is not given beforehand.

From the days of Newton until the previous turn of the century science provided ever more support to such a materialistic or realistic world view. The objects that we look at are really out there, regardless whether we observe them or not. The observer is secondary, and is equivalent to the intricately cemented piece of matter that constitutes its body.

But since the beginning of the 20th century science have started to point in another direction. The theories of relativity and quantum mechanics demand an observer to make it possible to motivate and understand its equations in a simple way. To express it more vividly: the living subject seems to be a fundamental part of the world.

I cannot help following the debate on these matters among physicists and philosophers of science. Even though science no longer provides support to a naively materialistic world view, many physicists and philosophers refuse to accept that this is so. They feel so comfortable with the pictures they have painted on the inside of their cocoons – pictures of objects that dance about independent from themselves – that they hold their ears if you knock on the outside of the cocoon and tell them that the world out there seems to be organized in a different way.

At this point someone will surely object that I contradict myself when I talk about a world outside the cocoon when I have just said that science suggests there are no objects independent from the living subject. But I use the term the world out there in a somewhat more subtle sense. For instance, the absence of objectively existing stuff does not preclude the existence of objectively existing laws of nature which govern what we see. We may be right or wrong when we interpret the world and its behaviour. To borrow the motto from The X-Files: The truth is out there.

My impression is that physicists who persist in their narrow materialistic world view rarely responds to, in a sober and pertinent way, those empirical facts and theoretical models that point in another direction. They do not even want to consider that they are wrong, or play for a minute with alternative world views to see where they lead. Instead, these are discarded with contempt, silence or with far-fetched theories with the sole purpose to uphold the preconceived world view despite all the facts that speak against it.

As an example of such a far-fetched theory I want to mention superdeterminisim. This idea has surfaced in order to explain away the strange behaviour of pairs of particles which are quantum mechanically entangled. Let me make a detour to explain what this means, and the return to superdeterminism, which has been called the final conspiracy theory.

That two particles are entangled may mean that if we examine one of the particles and find it in a certain state, the probability to see the other particle in a similar state immediately increases, regardless how far away it is located – be it in another galaxy. In a certain sense, this probability increase travels infinitely fast from one of the entangled particles to the other. Einstein called this phenomenon spooky action at a distance. The increased probability that the other particle will be found in a similar state as the first one means that the states of the two entangled particles becomes strongly correlated when we examine both of them.

There is not necessarily anything mystical or strange about such behaviour. We may imagine that the two particles have definite states to begin with, before we observe them, and that the probabilities we use to describe these states just reflects our ignorance about their actual states. In that case we may say that there are hidden variables whose values determine the state of each particle. Such a model is deterministic and the probabilities play no fundamental role. Therefore there is no need for a probability transfer from one particle to the other with infinite speed. The state we observe in one of the particles is already determined by the hidden variables. The increased probability to observe a similar state in the other particle is due to our increased knowledge about the values of the hidden variables as we observe the first particle, which, logically, affects the probability to observe a similar state in the second particle. But the fact of the matter is that this state is determined in advance, even if we do not know until we observe it.

A more detailed statistical analysis reveals, however, that such a deterministic explanation with hidden variables cannot give rise to such strong correlations between the entangles particles as seen in experiment. (This is true, at least, in all normal models with hidden variables, where these describe properties of the particles themselves, and go along with them as they move.) On the other hand, the experimental results agree perfectly with the predictions of quantum mechanics.

But in quantum mechanics there is no determinism; the state of the entangled particles are not given before we observe them, and the probabilities are fundamental quantities. We have returned to a model where an observation of one of the entangled particles immediately changes the state of the other, in terms of changed probabilities.

Ever more refined experiments rule out almost all other explanations of these phenomena than the quantum mechanical one. One of few remaining possibilities to avoid quantum mechanics and Einstein’s spooky action at a distance is to imagine that it is determined beforehand which observations of the entangled particles we are going to make. Then it may be determined that we are always going to do observations that seemingly confirm the strong correlation predicted by quantum mechanics, even though the correlation would have been weaker if we were able to choose our mode of observation freely.

But how on earth could something like that be determined beforehand, and when would it be determined? A research group in Vienna has recently challenged this idea by letting random colour variations in the light from a star located 600 light years away determine the way in which one of the particles in the entangled pair was observed, while colour variations in the light from another star located 2 000 light years away in the opposite direction determined the way in which the other particle was observed. The idea behind this arrangement was to push back the point in time at which the mode of observation has to be determined as far as possible. Since the light from the nearest of the two stars was emitted 600 years ago it must have been determined during the middle ages how the experiment in Vienna in 2016 would be carried out. An absurd thought.

Now we come back to superdeterminism. Rather than to imagine it was determined in an obscure way during a secret counsel below medieval vaults how scientists in Vienna would observe pairs of entangled particles in 2016, we may transcend to a general law of nature that we must always do observations that seemingly confirms quantum mechanics. In reality, though, the world is deterministic and can be described by a mathematical model with hidden variables. This would become clear if only the scientists could choose freely which experiments they are going to perform. Mother Nature is conspiring against us. She consistently hides her true face by just showing us carefully chosen glimpses, which we collect to a distorted portrait.

The truth is that very few physicists take superdeterminism seriously. But among those who do we find the Nobel laureate Gerard’t Hooft and some other highly talented people. How is it possible? I can only understand it psychologically. The metaphysical world view they have painted at the inside of their cocoons means so much to them emotionally that they refuse to accept that the world out there looks different when they look through the peep-hole in the wall of the cocoon drilled by science.

Aided by that metaphor we may express the idea of superdeterminism as follows. The physicist who is prisoner in her own world view does not want to believe what she sees when she looks at the world through a hole in the wall of the cocoon. She therefore gets the brilliant idea that what she sees, what seemingly contradicts her world view, is just a small picture that someone out there holds in front of the peep-hole. If this someone moved away this little picture so that the physicist inside her cocoon could look out freely, the world would look exactly like she imagined to begin with. But it never happens.

It is easy to make fun of other people’s follies. But each one of us carries a world view that gives meaning and direction to our lives, to our striving. If somebody tries to take it away we react instinctively and forcefully since we risk losing our foothold. We all know the firm grip of religious or political convictions, the impossibility to make someone change her mind by argumentation and finding examples contradicting this conviction. As long as possible we tweak our argumentation and reinterpret empirical facts to defend our position. Those who know me might say that I defend my standpoints more vigorously than most other people, whatever objections I face.

What is interesting is that this forceful and irrational (or rather a-rational) reaction is as evident in scientific battles as in religious or political ones. Evidently, the progression of science since the days of Newton has inspired a metaphysical materialism among Westerners that we adhere to and refuse to let go regardless what science itself suggests. We have become dependent on Newtonian materialism; to question it is to touch something very sensitive in our inner self.

I am psychologising. That is another habit of mine, apart from defending my positions stubbornly. Maybe it is because my dad was a psychologist. Freud, Adler and Skinner were often present at the dinner table when I was a kid, and they looked down on me from the book shelves.

As I grew up, I pulled the books from the shelves and started to read, Freud made a strange impression on me. He wrote with exquisite clarity, control and apparent logic, but the reasoning sometimes led to conclusions that seemed far-fetched or just nuts. I never managed to bridge the gap I sensed between the secure, authoritative voice that you like to listen to, and the fixated querulant who pursues strange theses in absurdum. Conspiracy theorists have a similar trait; they put forward facts and circumstances that support their theories in a seemingly waterproof way, and you are easily caught in the web they spin, but if you take a step back all of it appears far-fetched and stupid.

It is the same thing with superdeterminism. Those physicists who take this final conspiracy theory seriously must suffer from some kind of fixation; they must carry something they feel that they cannot afford letting go, someting that leads these highly intelligent people deep into the irrational quagmire with science and rationality as a beacon.

In his autobiographical book Memories, Dreams, Reflections Carl Gustav Jung devotes an interesting chapter to Freud and their interrupted friendship. Jung relates a conversation that he had in his youth with Freud, where the latter expresses a serious urging:

”My dear Jung, promise me never to abandon the sexual theory. That is the most essential thing of all. You see, we must make a dogma of it, an unshakable bulwark” He said that to me with great emotion, in the tone of a father saying, “And promise me this one thong, my dear son: that you will go to church every Sunday.” In some astonishment I asked him, “A bulwark – against what?” To which he replied, “Against the black tide of mud” – and here he hesitated for a moment, then added – “of occultism.”

I cannot help associating Freud’s conviction of his own sexual theory to some physicists’ conviction of the materialistic world view. Jung analyses Freud’s fixation to his own theory, and I would like to apply a similar analysis to these physicists:

One thing was clear: Freud, who had always made much of his irreligiosity, had now constructed a dogma; or rather, in the place of a jealous God whom he had lost, he had substituted another compelling image, that of sexuality. It was no less insistent, exacting, domineering, threatening, and morally ambivalent than the original one. […] The advantage of this transformation for Freud was, apparently, that he was able to regard the new numinous principle as scientifically irreproachable and free from all religious taint. At bottom, however, the numinosity, that is, the psychological qualities of the two rationally incommensurable opposites – Yahweh and sexuality – remained the same.

We just have to exhange the word sexuality for materialism. The latter should rather be described as amoral than morally ambivalent, though. But both are equally exacting. The former explains the entire human psyche, according to Freud, and the latter explains the entire world, according to its adherents.

But why would we, Westerners, like to exhange God for Materialism? Sexuality is an attraction of its own, apart from being scientifically irreproachable. But what is the allure of materialism? A possible explanation is that it is soothing. It teaches us that life is just some molecules that happen to gather into a human body for a short period of time, that love is just chemistry, that happiness is just a cocktail of neurotransmitters in the brain. The recurrent word just turns into a lullaby that makes us relax. We do not have to wrestle like Jacob with God, we cannot chose freely between good and bad, we have no responsibility for our choices before God or eternity. To question materialism becomes, in that light, an attempt to try to snatch a quilt from somebody’s bed, a quilt that makes life lukewarm and comfortable.

The world can be described as materialists say that it is, but it is not just like that, even though this description is a very effective tool to manipulate the world as we know it. The closer we examine matter itself, the more it dissolves before our eyes to mathematical abstractions that cannot be interpreted materialistically. The behaviour of the entangled pair of particles is an example of this fact.

Another explanation why belief in materialism stays strong despite these insights is its limitation; its keyword just spares us from infinity. When you think about it, there is hardly any other myth about the world that is easier to understand, and at the same time gives us the feeling that we understand everything. We get the feeling that we are done with the world. It allows us to lock ourselves into a small cocoon where we feel safe, at the same time as it creates the illusion to behold the entire cosmos thanks to the easily comprehensible world view that is painted on its inner walls.

I started this reflection by telling how infinity and the unknown outer space made me tremble as a little kid. A similar trembling and dread can be seen in the laboratory dogs in the Youtube film below, when their cages are opened and the see for the first time ever a large lawn in front of them, and the sky above. A came across this film a long time ago on Facebook, among all the touching and funny animal films that circulate there. But this film stayed in my memory. It is not only touching, but also existential. Just look how the dog watches the outside world with fear and wonder one minute and thirty seconds into the film, and look how the dogs hardly dare to touch the strange grass with their paws to begin with.

The advantages I see to stay in the cage of materialism are, as noted above, that it is soothing and that infinity is shielded. But there are serious drawbacks as well. First and foremost it becomes necessary to deny yourself and your fellow human beings. The living subject has no place in such a world view. Sure, some people say that consciousness can be explained as a collective result of the many intricate processes going on in certain complex systems, like the human brain. According to this line of thought, consciousness is emergent. But that is an empty word in this connection, even though it sounds beautiful. A five year old who has not yet been stuck in materialistic conceptions realises that subjective perceptions and the objective items of these perceptions are qualitatively distinct aspects of the world. It is impossible to deduce the ones from the others, just like it is impossible to deduce colours from sounds or letters from figures.

It is odd that so many people turn to materialism despite the self-denial that is required. It was logical as long as science suggested a strictly materialistic world; you had to try to accept that the world is as cold and mechanistic as it seemed to be. But science no longer points in that direction. Therefore there has to be an irrational force that makes us want to deny ourselves.

Is it psychologically necessary? Don’t we have the guts to look into each other’s eyes and say ”Hey, you exist and your existence means something! You are, you are not just. You cannot be reduced to something else, you are a miracle!” Are we so frightening that we better close our eyes before the mirror? Most of us have brushed our teeth in front of the bathroom mirror and suddenly happened to look into our own eyes. Then it may happen that your self-consciousness is heightened, like in an acoustic feedback; the primitive sensation that you exist causes vertigo. Then you are pushed away from yourself again, like if somebody pulled the cord from the socket to put an end to the feedback loop.

That the living subject is a fundamental aspect of the world does not necessarily mean that there is providence, warmth, a benevolent God. Is the thought of a cold and living world more frightening than the thought of a cold and dead world? Is that the reason why we turn to the second alternative? A living monster maybe scares us more than a mechanical monster?

When I categorically claim that materialists deny the living subject, I do not claim that they are cold and ruthless towards themselves and other people. Luckily, most of them do not live as they preach. To speak psycho-language again, they are mentally dissociated. Thought, feeling and action do not fit together. This dissociation is equally grave among materialists as among Christian creationists who at the same time are interested in science, and enjoy the fruits in the form of modern technology.

As I see it, the entire Western society is dissociated in this way. Newton concluded that the same laws of nature applied in heaven and on earth. The angles had to land on the ground, cut off their wings and make their living just like anybody else. From this insight there is a line of development to the ideal of equality that was forcefully expressed in the French revolution and in the U.S. constitution. We are equal before the law and have the same rights and obligations. The society of privileges crumbled. Rulers answered to the people rather than to heaven. The individual started to be seen as the fundamental unit of society and all individuals were assigned the same value.

At the same time there is no place for the living individual in a materialistic world view inspired by Newton’s physics. The word individual derives from Latin and means indivisible, but the only unit that is indivisible in a materialistic world is the atom, which is the Greek version of the same word. Man does not possess an indivisible soul but is equivalent to his body, which can be divided into ever smaller parts until we reach the level of the atoms. The behaviour of these atoms is determined by the laws of nature, and therefore the behaviour of human beings are completely determined by the same laws of nature. There is no place for the free will that is a prerequisite for Western justice, which is based on individual responsibility. The laws of society are therefore dissociated from the laws of nature that have inspired them.

Such dissociation at the root of a society cannot be sustainable in the long run. Then the right hand of the societal body does not know what the left hand does. When one of the dissociated conceptions finally crumbles under the pressure from the other, there will be confusion and aggression because of the lack of understanding of the underlying forces that has led to this situation.

The incompatible traits of individualism and atomistic materialism are exposed most clearly in the abortion debate. When does the foetus stop being just a collection of atoms in the womb of a woman, becoming an individual of its own? When does it acquire the right to its own life? The most stubborn abortion advocates do not even seem to realise that it is an existential problem that we have to tackle in one way or the other. Instead they repeat as a mantra that the woman has the right to her own body. But that answer is an non sequitur since it does not address the question. That is the way a dissociated individual reacts, a person unable to let two aspects of her conceptions meet and chafe.

Many people who lock onto a certain type of conception and refuse to try other perspectives are probably just afraid what will happen if they let go. Seas never sailed are filled by fantasy with sea monsters. If you admit that abortion is an existentital problem you are afraid that you are immediately transformed into a fanatical pro-life acitivst in the U.S. who foams with rage, waving placards referring to the Bible outside abortion clinics. If you would admit that personal existence is unfathomable, that we cannot explain the spark of life, you are afraid that you are immediately transformed into a spaced out new age type who cannot think straight.

Wolfgang Pauli is an example showing that this does not have to be the case. He is one of my favourite physicists. When he was thirty years old he underwent a crisis. He divorced, his mother committed suicide; he started to drink, quarrelled, and had intense dreams that worried him. To get help he contacted Carl Gustav Jung, who worked in Zürich, just like Pauli. Jung is considered to be the great mystic among the psychologists, with his ideas about the collective unconscious, about archetypes and synchronicity. Pauli embraced these ideas despite his scientific outlook, and he seemed to need them to understand himself and his dreams.

What is more, Pauli had no problems whatsoever to accept the new direction away from materialism that physics took as a result of the quantum mechanics that he helped to develop himself. He even predicted that future physics would move even farther away from these conceptions. Even so, Pauli was anything but a spaced out new age type who could not think straight. He was commonly known as the conscience of physics, and ruthlessly criticised colleagues who wrote papers, which lacked exact result and predictions, or which were logically and mathematically obscure.

Sure, his exact scientific personality and his need to explore subjective states of mind reveal a double face. But at least he tried to get the two mental poles to cooperate more harmoniously, to avoid dissociation. In a letter to Jung from 1934 he describes his dreams about wasps, and interprets the separate dark and bright stripes on their bodies as symbols of the two diametrically opposed attitudes in his own psyche. In the same letter he also writes:

The specific threat to my life has been that in the second half of life I swing from one extreme to the other […]. In the first half of my life I was a cold and cynical devil to other people and a fanatical atheist and intellectual ”enlightener”. The opposite to that was, on the one hand, a tendency toward being a criminal, a thug (which could have degenerated into me becoming a murderer), and, on the other hand, becoming detached from the world – a totally unintellectual hermit with outbursts of ecstasy and visions.

One may ask whether Western society has to go through another convulsion before the two incompatible principles of individualism and materialism that it is built upon become reconciled, in the same way as Pauli started to tackle the incompatible aspects of his personality only after a personal crisis. Let us hope that it is possible to dissolve the societal dissociation in a more harmonious way.

I always write much longer texts than I plan to do. I have talked about people who voluntarily live their lives in small cocoons to get peace and quiet, who paint pictures on their inner walls, which they confuse with the outside world. I have psychologised people and called them dissociated when they do not dare see all aspects of the world at once. Am I any better myself? No and yes! I am equally afraid of the world in which happen to find ourselves as anybody else, or maybe even more so. I have an equally large need to shield it, to sort the perceptions so that I only receive as many and as strong ones as I can handle. Probably I have spun thicker walls in my cocoon than most other people. But I try to avoid filling its inner walls with fantasy images, with myths. I rather stare at the bare walls. Now and then a ray of light finds its way through the threads which make up the wall, sometimes I see the contours of something moving outside. In that way I might learn something about the world. That is the way I want to live, that is the way I am able to live.